***WARNING: this post contains confronting and/or upsetting themes***

‘The nails and cuticles were coming off. The hair loose from the scalp, patches of greenish brown all over the body…the string of her nightcap was tied round her throat tolerably tight’. This was how Catherine Lyfield was found when her body was exhumed from the Merri River near Dennington, south-west Victoria. Lying in the outhouse of the Shamrock Hotel in Port Fairy where the inquest was held, the middle aged woman was severely decomposed with a number of loose teeth and a damaged skull.

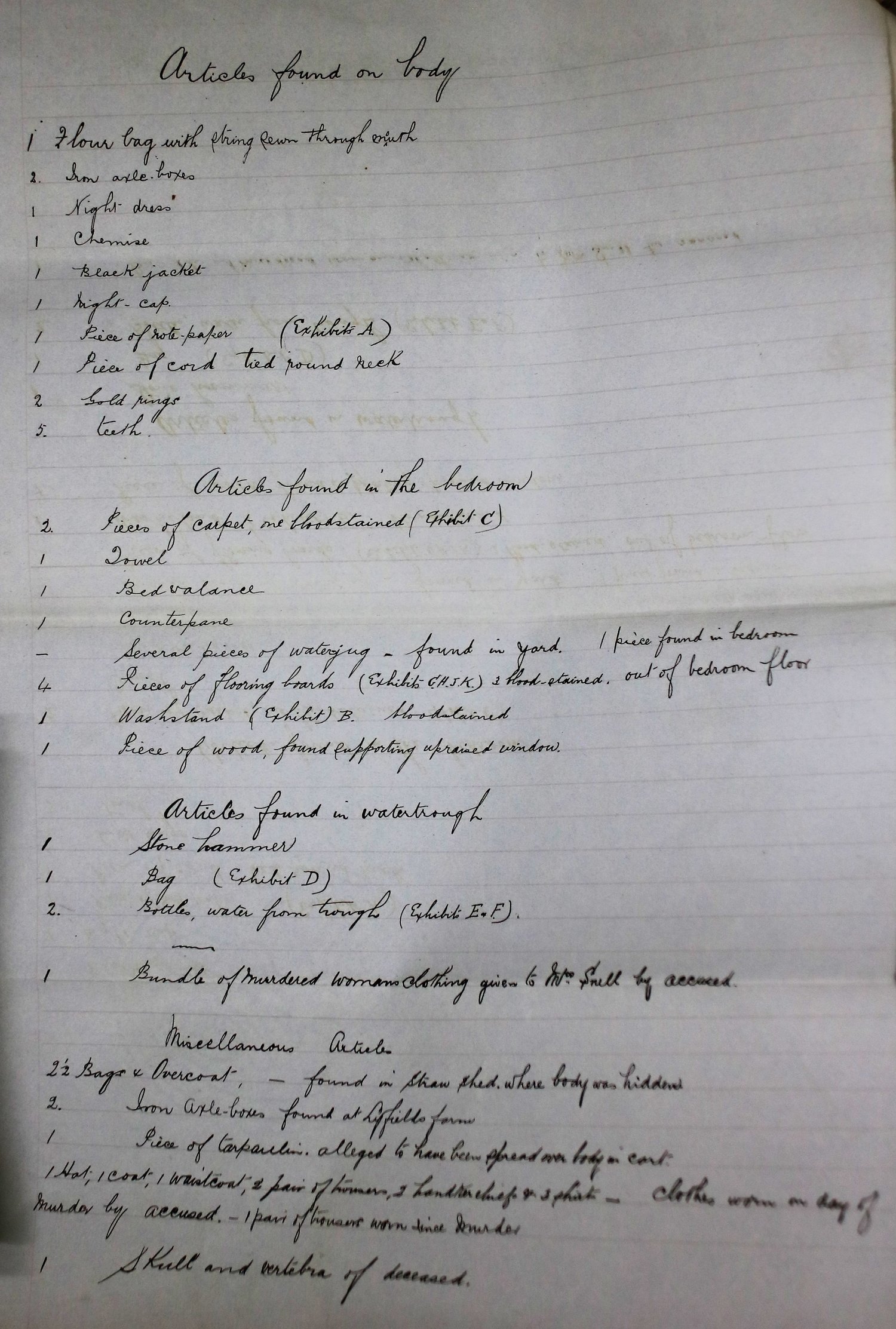

Henry Lyfield was a dairy farmer from Rosebrook, about five kilometres north-east of the seaside town of Port Fairy. Henry’s first wife Sarah had died in 1864 at the age of 43 years old; their eldest living child was sixteen and their youngest child was just a year old. Three months later the 36 year old father of eight re-married. His second wife was Catherine Harper, a nineteen year old servant girl.

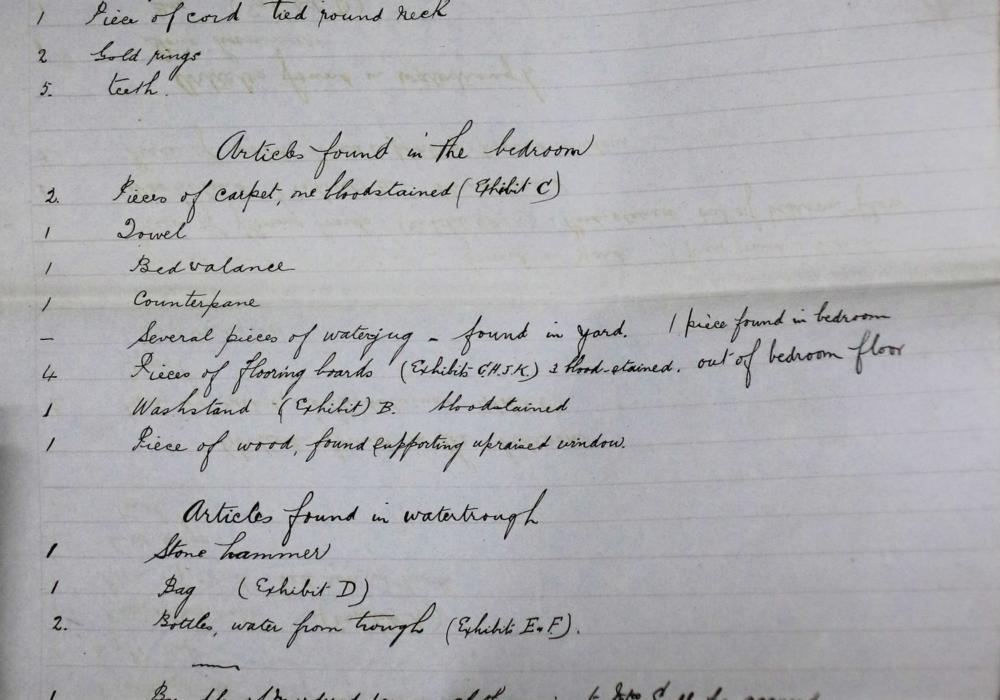

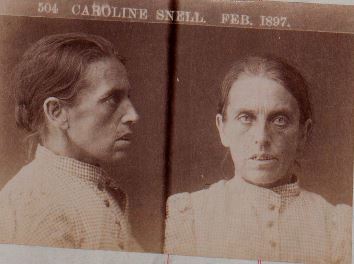

‘Articles found on body’. VPRS 30/P0, Crimal Trial Brief, Unit 1121, Item 619.

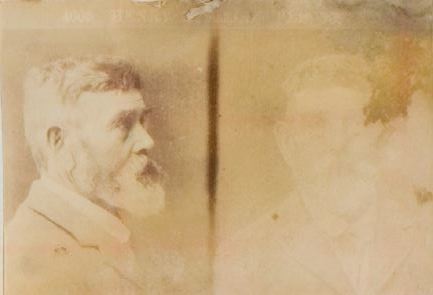

Caroline Snell was Henry’s third child and had moved back into the family home with her father and stepmother after her husband Williams’ death. Caroline and her thirteen year old daughter Elizabeth joined her older sister Jane back at the family dairy farm. The three would often overhear Henry and Catherine fighting, with it frequently becoming violent. At least once Henry began hitting his wife to the ground, choking her and threatening to kill her.

One evening in mid-October 1896, Caroline, Elizabeth and Jane were all in bed by 8 o’clock; the three sharing a room next door to Henry and Catherine. In the early hours of the following morning the women were woken by the sounds of low screams. Thirteen year old Elizabeth, ‘heard the sound once, like something hitting against the [adjoining] wall…a noise like somebody having a struggle’, shortly followed by the sounds of heavy footsteps. By 5 o’clock that morning the three women and Henry went about work as normal milking the cows, upon their return to the house Henry handed a bundle of soiled clothes to Caroline to wash, stating that, ‘here are the clothes, she will never want them again’.

Peering into the other bedroom at the front of the house, usually shared by the couple, Elizabeth spotted Catherine lying on the floor, covered up, unmoving.

The following evening Caroline was awoken by the sound of footsteps in the front room. Claiming that she ‘heard a noise like someone dragging a heavy thing about the floor towards the front outside door’, she went to inspect that morning to no avail. Walking in to the shed the next day to collect some potatoes for the family’s next meal, Caroline noticed ‘something covered over with straw and two bags…and saw a part of the face of a human being’. Caroline had uncovered the body of her stepmother Catherine.

Meanwhile, Henry was going about his daily life, telling people that his wife had walked out on him and he’d not heard a word from her.

By 26 October 1896, friends and peers were having to identify the remains of Catherine and a post-mortem examination was being undertaken on her mangled and decomposing remains.

In February the following year the case had to be moved from the local county court in Warrnambool to the Supreme Court in Melbourne. Henry Lyfield and his daughter Caroline Snell had been charged with the murder of Catherine Lyfield and had both pleaded insanity. Caroline had confessed to assisting her father in murdering her stepmother after he threatened her. Henry was said to have been annoyed at his wife for keeping a strict eye on him and his movements with his daughter. Whilst beside her bed praying, Henry moved behind his wife and ‘threw a string round her neck. She struggled and screamed’ and Caroline ‘struck her with a hammer’. Killed, she was then taken to the Merri River and her body dumped.

Catherine’s need to keep a close eye on his husband was not because she was a possessive wife, it was because she was aware of the incestuous relationship that was going on between father and daughter.

During the proceedings much more came to light than domestic violence and the murder of Henry’s second wife, Catherine. Journalists, sitting in on court proceedings reported that ‘Lyfield, according to the testimony of his own daughter and granddaughter, [was] a triple murderer, and [had] habitually been on terms of criminal relations first with one and subsequently with both of them…two children [had been] born as the result of the incestuous intercourse with the daughter [and] the inhuman father is alleged to have killed them in cold blood and buried them on this farm’, the third and only surviving child grew up believing her father was William Snell.

On 15 February 1897, Henry Lyfield was found ‘not guilty on the grounds of insanity’. He died in 1901 at the age of 71 years old of natural causes in Melbourne Gaol.

Caroline Snell was ‘unable to plead on grounds of insanity’, and in March 1917, twenty years after first stepping into the Melbourne Gaol Female Prison, she was transferred to Melbourne Benevolent Asylum.

Phoebe, April 2018

Sources:

PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 1121, Item 619

PROV, VPRS 515/P1, Unit 51, Henry Lyfield, Prisoner no. 27794

PROV, VPRS 516/P2, Unit 12, Caroline Snell, Prison no. 6495

Evening News (NSW)

Western Champion and General Advertiser for the Central-Western Districts (Queensland)

Horsham Times (Victoria)

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Queensland)

National Advocate (NSW)

Adelaide Observer (SA)

Ballarat Star (Victoria)

South Australia Register (SA)